The Ark: 125 Years of Service

Nestled among the trees and Georgian architecture on East Campus stands a self-effacing, white clapboard building that predates the century-old Duke we know today. Hiding behind the Wilson Residence Hall, the Ark quietly watches students as they pass by, its austerity of design and understated elegance belying the richness of stories and traditions retained within its walls.

One of the oldest buildings on campus, the Ark witnessed the birth of Duke basketball, helped feed and clothe our students and provided a haven for physical education and social recreation. It is also the birthplace of Duke’s Dance Program, and proudly stands today as the heart of dance-making and research at Duke.

In the beginning

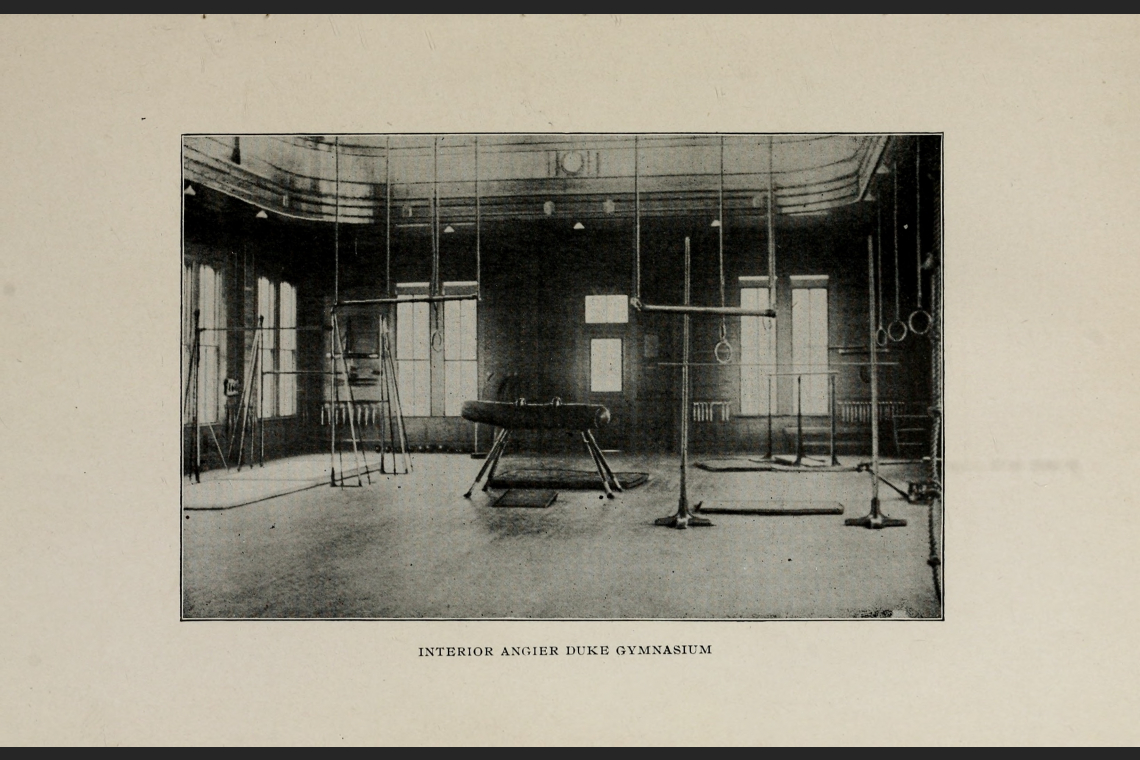

The beguiling building began life as an intramural gymnasium situated on land where Blackwell Park, home to one of the best half-mile horse tracks in the South, once stood. Resurrected from reclaimed wood from the park’s grandstand and named after Benjamin N. Duke’s then teenage son, the Angier Buchanan Duke Gymnasium opened in 1899. One of the first college gymnasiums in the state, it was equipped with all the modern accoutrements the young men of Trinity College needed for physical education.

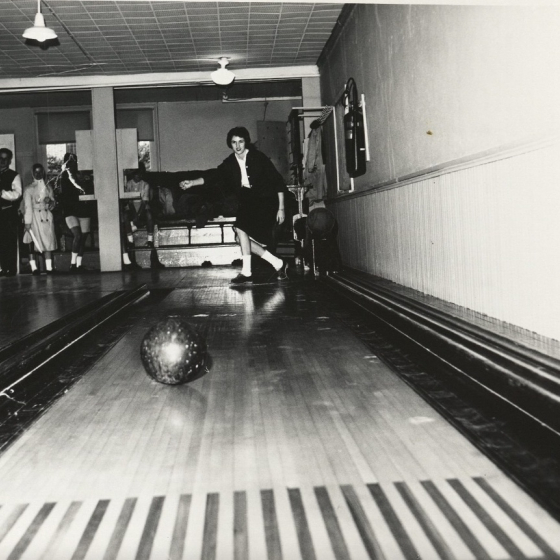

A running gallery, trophy room and dressing lockers occupied the top floor, which looked down on an expansive main level that housed state-of-the-art equipment: a double trapeze, a pommel horse, two horizontal bars, a striking bag drum (equivalent to a modern punching bag), parallel bars, traveling rings and a rope ladder. Two bowling lanes were in the basement, along with a swimming pool — which was less of a pool and more of a large, round wooden tub prone to leaking.

Albert Whitehouse, the gym’s first director, oversaw the students’ physical training and presented public gymnasium exhibitions and contests, where students could display their athletic prowess. Whitehouse stepped down in 1902 and was replaced by Wilbur Wade “Cap” Card, of Card Gymnasium fame, who brought basketball to campus four years later.

On March 2, 1906, the Angier Gym welcomed Wake Forest and 125 spectators to Trinity’s first intercollegiate basketball game. Card cleared the exercise equipment from the main floor and installed backboards and hoops at both ends of the mere 50- by 32-foot court, where Wake Forest was victorious, 24-10. Four days later, the Trinity Chronicle attributed the loss to the inexperience of the home team but noted: “The game was an unusually clean one from start to finish with very few fouls, and roughness was rare.”

The rapidly expanding Trinity student body eventually outgrew the Angier Gym, and when the larger Alumni Memorial Gymnasium was completed in October 1923, the “old gym” embarked on its second chapter.

Feed and clothe the people

Pete Dorton, owner of the local Goody Shop restaurant, approached Trinity leadership with his desire to convert the main floor of the soon-to-be vacant gym into a modern cafeteria, something sorely lacking on East Campus at the time. Trinity Cafeteria, or “Pete’s Place,” opened in the fall of 1923, offering student meal plans as well as banquet facilities. That same year, the Athletic Laundry and Pressing Club set up shop in the basement, providing a full range of laundry services and shoe repair to the men of East Campus.

The completion of the Duke Unions in 1927 brought more meal options to East Campus, and Pete’s Place vacated the following year. The university laundry then expanded to occupy the entire building until the spring of 1930, when it pulled up stakes and migrated with the men to the newly built West Campus.

Post exodus, East Campus became the Woman’s College, and the overlooked gym disappeared from campus records. Possibly relegated to campus storage, it was soon earmarked for demolition. Enter Evelyn Barnes, who took the initiative to rescue the building and write the Ark’s third chapter.

Keepers of the Ark

Evelyn Barnes wore many hats at the Woman’s College: house mother for Alspaugh Residence Hall, advisor to the Music Study Club, director of the Woman’s College orchestra and sponsor/advisor for Sandals — the sophomore honor and service sorority formed in 1932. Barnes recognized a need to build community in the newly formed Woman’s College and understood most cash-strapped students couldn’t afford off-campus entertainment during the Great Depression.

Approaching Alice Baldwin, dean of the Woman’s College, and W.A. Tyree, director of business, Barnes suggested turning the vacant laundry into a recreational center, with Sandals overseeing the building’s upkeep and serving as hostesses. Baldwin and Tyree liked what they heard, and Sandals welcomed its new charge with open arms. And so began a monumental year for the old gym.

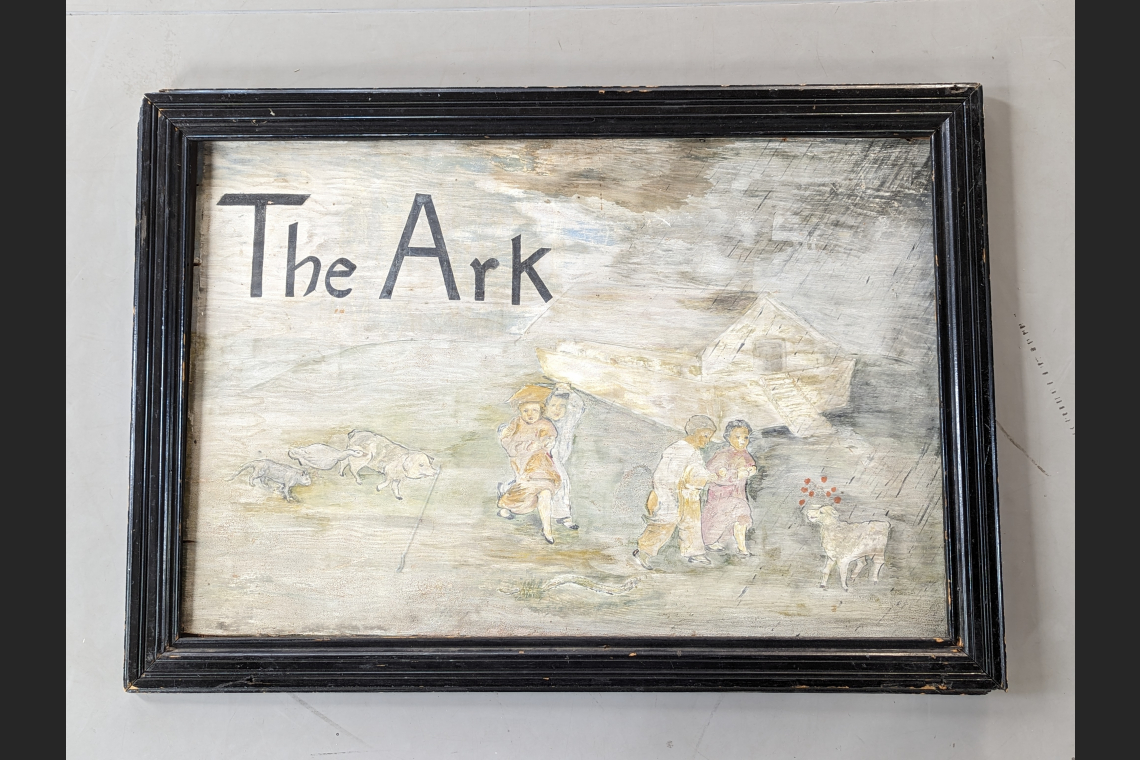

The sorority voted to rechristen the building “the Ark” based on comments from Hope S. Chamberlain, house mother of Pegram Residence Hall. People had always entered the building via a narrow bridge, and as she watched students cross on the gangway with room for only two at a time, Chamberlain remarked how it reminded her of “wolves and sheep” entering Noah’s Ark.

She never clarified which co-eds were wolves and which were sheep. But she did paint a sign depicting her version of the ark which hung above the building’s entrance for decades — and now lives in the building.

1933 marked the official unveiling of the Ark as the latest hotspot on East Campus. Over winter break, the wood floor had been scraped, sanded and refinished to prevent dance slippers from snagging on splinters. An additional bowling lane was installed, along with ping pong tables, wicker furniture and lighting. Sound proofing was added to the ceiling, walls were painted and curtains sewn and hung.

Guests enjoyed the latest songs from a Victrola radio or from live big bands during the weekends, while hostesses kept their Ark stocked with the latest records, magazines and card games. Ping pong tables occupied the upper running gallery-turned balcony, and each incoming group of sophomores built upon the improvements from prior classes. Over the years, the ping pong tables joined pool tables in the basement, a juke box eventually replaced the victrola and pickled pine paneling was added to the main floor’s walls.

The sorority’s commitment to the Ark was admirable. Sophomores worked tireless to raise the funds needed to keep the building in order, and their efforts were fruitful. Throughout the 1930s, it was common to see hundreds of co-eds pack the Ark for weekend dances, and the 1939 Alumni Register declared the Ark, “one of the most popular and attractive spots on the Woman’s Campus.”

But post World War II generational shifts took their toll, and sentimentality was replaced by practicality. In a Sandals Annual Report from 1950, the Ark was described as “the most tedious and most unrewarding job that Sandals have [has].”

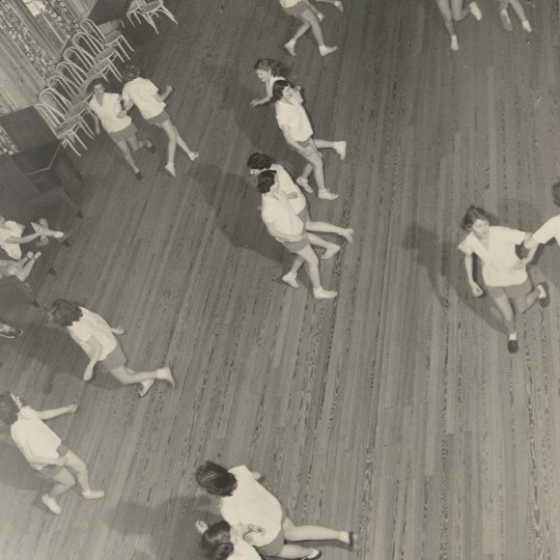

The writing was on the pickled pine walls, and by 1952 Sandals would open the Ark by request only. The sorority eventually returned the building to the college, where is became a catchall for East Campus: cheerleader auditions, Hoof ‘n’ Horn rehearsals, custodial retirement parties — even faculty square dance practice. Ironically, as the student body outgrew the Alumni Memorial Gym, physical education returned to the old gym as the Women’s Athletic Association used the Ark for required body mechanics and dancing classes.

In the mid 1950s, the Ark also became the audition, rehearsal and occasional performance venue for the Terpsichorean Club, the modern dance student club led by the indominable Julia Wray. Wray quickly understood the relationship the Ark could have with dance, as she began to write the building’s current, and most enduring, chapter.

To everything there is a season

Julia Wray joined the Physical Education Department with the Woman’s College in 1955 and was instrumental in redefining how dance was seen on campus. Rather than an academic credit for first-year students, Wray championed for dance to be seen as a true discipline, moving it out of the gym class and into the curriculum. The college designated the building for the Dance Program, and the Ark quickly became its official nerve center, with Wray serving as director until her untimely passing in 1989.

Wray was also faculty liaison to the American Dance Festival (ADF), which moved its summer fête from Connecticut to Duke in 1978, utilizing the Ark for studio space. Celebrating 47 years in Durham this summer, the venerable dance festival has welcomed 200-300 dance students to campus each year. The Ark is still seen as hallowed ground for many of the world’s celebrated dance luminaries, who hold the building as a coveted space for dance making.

“Our dancers walk into that magical space and absorb the palpable history of those who came before, and that helps them become future dance makers,” explains Jodee Nimerichter, executive director of ADF. “The Ark doesn’t look like any other place, and ADF sees it as a large, expansive container of history that holds value to anyone who steps on the floor.”

For Barbara Dickinson, dancing in the Ark has been nothing short of magical. Now an emerita professor of Dance, she continues to participate in productions and regularly presents works-in-progress at the Ark. Dancing in the building, with its expansive ceiling and two levels of tall windows on the north- and south-facing walls, gives her the feeling of being in a space that simply goes on forever. She appreciates the surrounding nature and the high ceiling, suggesting a spiritual space where Dickinson can project herself beyond her own physical limitations.

“Artists from all over the world have danced in the Ark,” she adds, “and their creative vibrations have permeated the walls.”

She also appreciates what the building symbolizes.

“The Ark was a gift to the Dance Program because of the hard work and persistence of Julia Wray, who was determined to make dance at Duke something meaningful.”

Jane Desmond came to Duke in 1982 as an artist-in-residence with the Dance Program and fondly recalls her years of teaching in the Ark. By that time, the building was buzzing with dance classes and repertory rehearsals on the main floor. Student groups used the basement — now void of ping pong and bowling lanes — for evening rehearsals.

“When I was teaching technique classes with leaping combinations, I could really use that vertical space to inspire people,” she explains. “Those walls of windows were also so crucial, it was light from all around.

I'd love to see that space retain its identity with all those windows and openness, while adapting to whatever technology will benefit future dancers the most.”

Perseverance

Approaching 125 years of faithful service, the Ark continues to welcome ADF students each summer. In 2018, when Duke inaugurated the Rubenstein Arts Center, the Dance Program was able to relocate some movement courses to those facilities, enabling the Ark to house the Masters of Fine Arts in Dance: Embodied Interdisciplinary Praxis (MFAEIP), the only Dance MFA among the Ivy+ schools. The Kenan Institute for Ethics’ Laboratory for Social Choreography, led by Professor of the Practice Michael Kliën, currently maintains space in the lower level, along with dance rehearsal space and a classroom.

The building’s legacy of service to students isn’t lost on Sarah Wilbur, director of the MFAEIP and associate professor of the practice of dance.

“I hear our students describe her [the Ark] and defend her, advocate for her and protect her,” she explains. “I don't use this term lightly, but she feels like a sanctuary to a lot of our MFA students.”

Her sanctuary also nurtures a freedom to create that students might not experience anywhere else on campus — and that was purposeful. From new works to thesis projects, the Ark gives students the confidence and permission to explore.

“This is a strategically protected space for advanced-level creative dance research and experimentation,” Wilbur shares. “The Ark is that messy space artists need to invent work while exploring their wildest ideas.”

And along with the messiness, sweat and energy from everyone who’s ever dribbled, jitterbugged or grande jetéd on the floor, Wilbur shares that the building also holds great sentimentality. It isn’t uncommon for faculty teaching in the Ark to see people who are visiting Duke peek through her windows during a class, grabbing a glimpse and sharing a memory of their time dancing on her floor.

The narrow gangway has been replaced with a generous and more welcoming flight of stairs, but otherwise, the Ark has changed little over the century. Despite the windows propped open in the hopes of catching a cross breeze, the air inside still feels heavy during the dog days of summer, as the familiar scent of aged wood lingers in the stillness.

The pickled pine and the evidence of Pete and Angier’s legacies are still there — along with some spots that could use a carpenter’s attention. And while she’s gathered a few aches and pains over the century, the Ark maintains her architectural anachronism as she’s comfortably settled with her lot at Duke.

When contemplating the grande dame’s next chapter, Wilbur shares, “Because of the MFAEIP’s interdisciplinary dance and embodied research, Dance faculty and students are exploring novel ways to host movement-based programming and research at the Ark, from all corners of Duke’s campus.

So, I hope she’s preserved, both physically and historically — but a few modern updates wouldn’t hurt.”

If you would like to share stories and photos of the Ark, from whatever chapter of her life, please reach out to: margo.lakin@duke.edu

This article could not have been possible without the archivists and collections at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library — and the incredible knowledge and gracious assistance from Rebecca Pattillo, assistant university archivist.